I’ve read a couple of books by Brian Kindall by now, and that’s been enough to understand his commitment to flawed protagonists who have a tendency to talk more than they think – or, to be more accurate, to be so persuasive to themselves that they don’t always see things as logically as they do. In both Fortuna and the Scapegrace and Delivering Virtue, Kindall gave us his variation on True Grit as filtered through a priapic, narcissistic poet more focused on his own pleasure than the good of anyone around him, all viewed through his own unique perspective.

Now, in Escape from Oblivia, Kindall brings that idea into the contemporary world while paying homage to men’s pulp stories, and the results are just as successful, if a little harder to take. Our protagonist, Will Kirby, is going through a midlife crisis, even if he’s not quite as aware of it as we are; no, to him, all of this is normal, from the awkward flirting with the library clerks to his obsession with pulp author Dick Zag, whose work fills Kirby with a weird “nostalgia” for a world that never was – one where women throw themselves at men, adventure allows them to prove themselves, and men are defined by actions, not their families, their words, or their “feelings.” Who cares if that world never really existed (something Kindall nicely underlines during Kirby’s research on Zag) – wouldn’t it be nice to be a man’s man, in a man’s world?

Without the absurdities and excesses of Virtue and Fortuna, Oblivia sometimes struggles to make Will as likable as Didier Rain was; while Rain’s story was off-kilter enough to allow us to enjoy Rain’s self-serving narration, Kirby’s down to earth existence makes his selfishness and extreme justifications a little harder to take, especially as the book reaches its midpoint and Kirby stomps on the gas of this crisis. Add that to a situation that felt like absurd male fantasy that seemed to reward Kirby for his actions, and I wasn’t so sure about Oblivia…

…until Kindall does something wholly unexpected, and does so in a way that makes the book fall into sharp focus and allows Kindall to deliver a moral without ever moralizing or stopping the book cold. I don’t really want to give away what happens here, simply because it caught me so off-guard and drew me back into a character I was struggling to empathize with; suffice to say, Kindall turns Escape from Oblivia into a wholly different kind of book, one that allows him to continue his trend of interrogating male fantasies and obsessions in a new way, finding the flaws in them while also refusing to judge his male characters – oh, they may be flawed and solipsistic, but they’re also human, and Kindall allows them to be both, trusting his readers to make judgments for themselves instead of being handed the morality of their tales.

I don’t think I liked Oblivia quite as much as the Didier Rain books, whose “tall tale” vibes made them a bit more enjoyable and engaging, but there’s still much to appreciate about Oblivia, from Kindall’s sharp ability to write an internal monologue to his commitment to flawed male characters unable to get out of their own perspective. And that final act is so solid that it single-handedly raises the book immeasurably, taking the story in a new direction while never looking away from the issues it had been dealing with all along, and even coming to a surprisingly optimistic step forward by the end. Rating: ****

Aidan Lucid’s The Scavenger is the first of his “Hopps Town duology,” which is the sort of thing that always worries me a bit when I get a review copy of a book; it’s the kind of subtitle that makes me worried that I’m going to get the first half of a story and be asked to review what’s clearly an incomplete tale. Luckily, that’s not the case with The Scavenger; while the story has some jagged edges and janky parts, it delivers a nicely self-contained tale with engaging characters and a good enough story to draw you in.

As the series title suggests, The Scavenger takes place in a small town called Hopps Town, where we’re rapidly introduced to three teenagers: Jared, a young African-American man who’s dealing with being judged for being out and gay; Jessica, whose abusive and awful home life has her motivated to just get out as soon as she can; and Adrian, who…well, honestly, Adrian is just kind of “there” for the most part, dealing with relationships and crushes like any teenage boy. But when the trio ends up making a wish in an abandoned fountain, life starts getting very, very strange – and then getting rapidly out of hand, as it becomes clear that they’ve tapped into something far more than they bargained for with those wishes.

The Scavenger has some good ideas in there, and by the time you get to the end, you can see the overall structure of the book – the way the opening dream sequences set up the overarching story to come, the idea that Lucid is setting up for book two, etc. But that doesn’t keep the book from feeling a bit disjointed as you go along, as new characters appear awkwardly to save the day, or one minor character appears and abruptly gets a flashback to a key moment in her life for no major reason, and that has nothing on the abrupt turn into becoming a very Christian-driven exorcism story about halfway through, something the rest of the book only barely mentions. There’s also definitely some areas where Lucid is trying but probably could have used some outside opinions on things – for instance, in what world do teenagers still use FaceBook for anything?

So, yes, there are some issues here. But in general, The Scavenger works well, paring back the excessive world-building and narration that bogged down his previous book The Lost Son and focusing instead on moving the story quickly along. And if there are some weird elements along the way that feel like they could use some revising (the focus on predatory behavior against young girls feels out of place and extreme in the book tonally), there’s also an engaging idea here and some genuinely solid sequences (the standout is the moment in which we’re forced to realize just how bad Jared’s wish is going to break bad). It’s far from perfect, but it’s still an engaging and entertaining read. Rating: *** ½

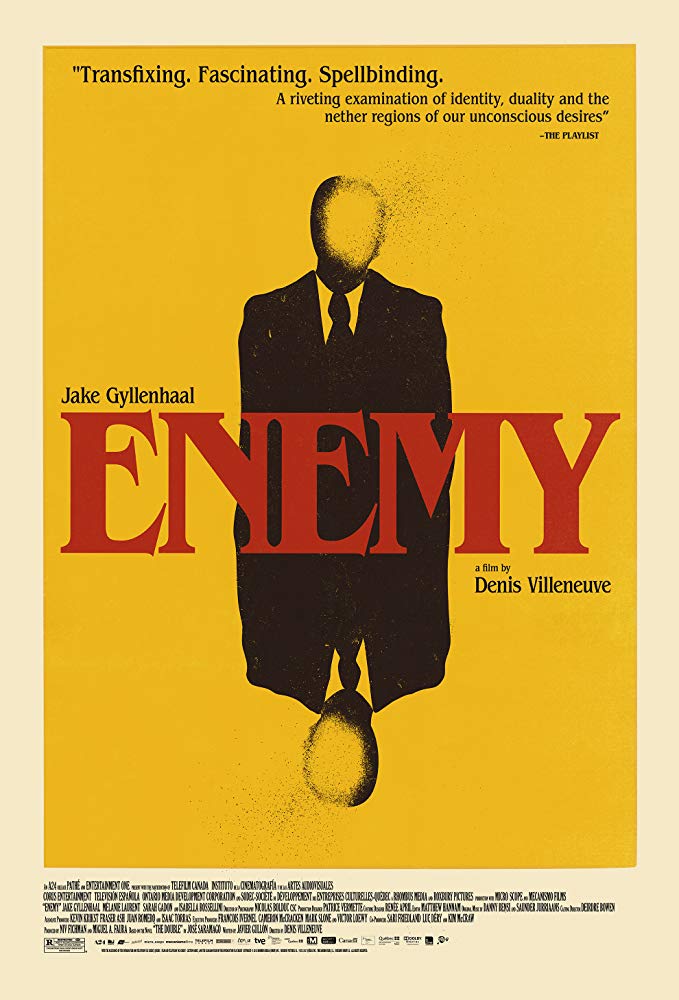

Denis Villeneuve has made a name for himself in recent years with moody, complex cinematic fare that revels in complexity and depth. With movies like

Denis Villeneuve has made a name for himself in recent years with moody, complex cinematic fare that revels in complexity and depth. With movies like  It’s somewhat unexpected to find William Wyler – the respected director who made The Best Years of Our Lives, Ben-Hur, Roman Holiday, and other classic film staples – directing The Collector, a deeply strange film that feels more in line with Peeping Tom than it does your stereotypical classic film fare. (Of course, Wyler also helmed The Desperate Hours, so it’s not like thrillers are unknown territory for him.) The Collector sometimes feels like it doesn’t have the courage to be as unsettling and squirm-inducing as the material should be, but in many ways, his more formal approach only underlines the twisted dynamic of the movie, making that tagline of “almost a love story” all the more appropriate.

It’s somewhat unexpected to find William Wyler – the respected director who made The Best Years of Our Lives, Ben-Hur, Roman Holiday, and other classic film staples – directing The Collector, a deeply strange film that feels more in line with Peeping Tom than it does your stereotypical classic film fare. (Of course, Wyler also helmed The Desperate Hours, so it’s not like thrillers are unknown territory for him.) The Collector sometimes feels like it doesn’t have the courage to be as unsettling and squirm-inducing as the material should be, but in many ways, his more formal approach only underlines the twisted dynamic of the movie, making that tagline of “almost a love story” all the more appropriate. The easiest comparison to make that conveys the feeling of Gerald Kargl’s Angst is to the seminal Henry, Portrait of a Serial Killer. Preceding Henry by a few years, Angst is a raw, unflinching depiction of the mind of a psychopath, following him from his release from prison all the way through his invasion of an isolated country home and his crimes committed therein. And yet, while Henry gave us a killer who could present himself as calm and rational, the madman at the core of Angst is something wholly else – a damaged, disturbed individual so driven by his psychosexual hangups and desires that every moment is taken up with his own insanity and violence. This isn’t Hannibal Lecter, or even Francis Dolarhyde – this is someone simultaneously pathetic (in the most literal sense) and nightmarish.

The easiest comparison to make that conveys the feeling of Gerald Kargl’s Angst is to the seminal Henry, Portrait of a Serial Killer. Preceding Henry by a few years, Angst is a raw, unflinching depiction of the mind of a psychopath, following him from his release from prison all the way through his invasion of an isolated country home and his crimes committed therein. And yet, while Henry gave us a killer who could present himself as calm and rational, the madman at the core of Angst is something wholly else – a damaged, disturbed individual so driven by his psychosexual hangups and desires that every moment is taken up with his own insanity and violence. This isn’t Hannibal Lecter, or even Francis Dolarhyde – this is someone simultaneously pathetic (in the most literal sense) and nightmarish. Jack Ketchum – whose real name was Dallas Mayr – was an utterly unique, brutally intense horror writer, one whose work was unlike almost anything else out there. Ketchum, who died last week, was an author who was fascinated by violence – its effects on the human body, yes, but also the things that can lead people to commit such horrible acts. His novel Red, for instance, traced how a man could be treated in such a way that could lead him to horrible acts of revenge, while The Lost followed damaged characters until a public nightmare is unleashed. And while Ketchum made his name with the nightmarish cannibal tale Off Season, he’s probably most well known – and most infamous – for The Girl Next Door, which holds the rare distinction of being one of the most upsetting, horrific, disturbing books I’ve ever read. It’s a fictional retelling of the Sylvia Likens murder, a case I advise you not to Google unless you’re prepared for the horrors to come. And this is not exaggeration. Suffice to say, it’s about a girl who is kidnapped and held in a cellar, and the way people around them slowly find themselves open to horrific acts of cruelty and brutality.

Jack Ketchum – whose real name was Dallas Mayr – was an utterly unique, brutally intense horror writer, one whose work was unlike almost anything else out there. Ketchum, who died last week, was an author who was fascinated by violence – its effects on the human body, yes, but also the things that can lead people to commit such horrible acts. His novel Red, for instance, traced how a man could be treated in such a way that could lead him to horrible acts of revenge, while The Lost followed damaged characters until a public nightmare is unleashed. And while Ketchum made his name with the nightmarish cannibal tale Off Season, he’s probably most well known – and most infamous – for The Girl Next Door, which holds the rare distinction of being one of the most upsetting, horrific, disturbing books I’ve ever read. It’s a fictional retelling of the Sylvia Likens murder, a case I advise you not to Google unless you’re prepared for the horrors to come. And this is not exaggeration. Suffice to say, it’s about a girl who is kidnapped and held in a cellar, and the way people around them slowly find themselves open to horrific acts of cruelty and brutality.